Analytical Techniques — Final Paper

June 30, 2024

Lyrical and Harmonic Emotion in Moxy Früvous’s “Fly”

“Fly” is the third track on Moxy Früvous’s 1995 album Wood. Founded in Toronto in the early 1990s, Früvous signed with Atlantic Records and released their first album in 1993, and remained active until 2001 (McLean, 2013). Wood was Früvous’s attempt to break away from the politically satirical music for which they had become known. The band has described Wood as more “introspective,” “cohesive,” and “casual” than their previous writing (Harvey, 1995). Much of the album’s music explores themes of troubled or unsuccessful relationships. “Fly” is one such exploration (Example 1). Despite Wood’s mixed reception from the public, the song was rerecorded on 1997 live album Live Noise.

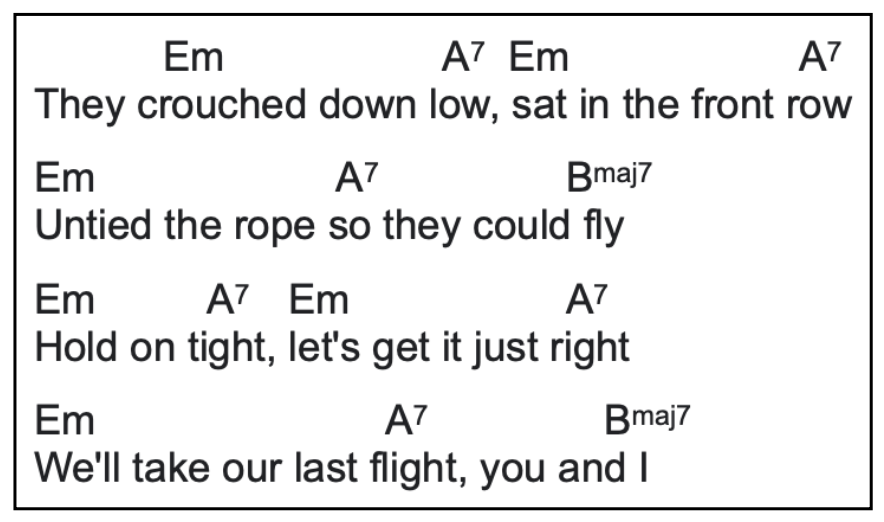

Example 1: Lyrics of “Fly” (Moxy Früvous, 1995).

“Fly” uses descriptive imagery about an amusement park to tell the story of a couple in the final moments of their relationship. As lead singer Jian Ghomeshi says in the opening seconds of the Live Noise recording, “here’s a song… that’s about the moment when you realize that someone that you really love, that you really care for — when you both realize that you’re just not right for each other. It’s a song about that feeling” (Moxy Früvous, 1997). The narrator begins by reflecting on the passion that once existed between the two protagonists, acknowledging that the passion has since passed. Much of the song uses a metaphor of an amusement park and a rollercoaster: the couple visits an amusement park at night, without any coins to use on games or rides. It is implied that they board and ride a rollercoaster without having paid. Later, they get a bit more emotional and end up taking off their shoes for a moment of intimacy. The chorus, which repeats for most of the remaining duration of the song, revisits the rollercoaster ride. The track uses bass, guitar, harmonica, tambourine and other rhythm, and lead and backing vocals. The texture is lighter in the verses, the guitar exclusively finger-picking its harmony, while the chorus is denser and strummed.

In this paper, I use Lori Burns’ lyric analysis (Burns, 2010) and Mark Spicer’s theory of tonal ambiguity (Spicer, 2017) to show that “Fly” manipulates metaphor, status transformation, and tonal fragility to create moments of emotional tension and release. This emotional content, in turn, reinforces and amplifies the song’s narrative. The pervasiveness of this messaging, as well as the clear alignment between lyrics and harmony, increases the song’s emotional impact upon the listener.

The lyrics to “Fly,” like those of most Früvous songs, are relatively cryptic and indirect. A line-by-line poetic analysis of the lyrics, however, elucidates both the true narrative and the ways in which the amusement park imagery supports it. From the outset, the listener has to work in order to uncover the meaning of the text. The opening line references As the World Turns, a 54-season soap opera (IMDb.com); if a person feels like they have been living in soap-opera levels of drama, the narrator says, their reckoning with their relationship should be simple. “Every little child learns / If you can’t see dreams, your eyes are blind”: it is (or should be) common knowledge that if someone struggles to dream about their future, they might be on the wrong path. “Was it just a fool’s impression? / Such an antiquated passion”: the love that the protagonists once had for each other seems like a mistake, and has long since past its prime.

Beginning in the second verse, the narrator uses an amusement park as a metaphor for various aspects of the relationship. To “ride the midway” — a “midway” being the section of an amusement park containing sideshows, games, and concessions (Merriam-Webster) — is to go through the motions of the relationship, perhaps during a date or a hookup. They didn’t “bring coins to this amusement park,” signifying their lack of emotional commitment. These analogies continue into the chorus, where the rollercoaster comes to represent the breakup itself. The couple “crouched down low, sat in the front row / Untied the rope so they could fly” on a rollercoaster; at the same time, they are untying themselves from each other, leaving no strings attached. This analogy is fitting; there can be a great deal of anticipation leading up to a breakup, especially if those involved have long observed the pitfalls of their relationship, as is the case here. This anticipation is followed by a brief period of free-fall, a simultaneously terrifying and thrilling relief of the previous tension.

The third recorded verse, beginning with “So they cried…”, is slightly more transparent. “So they cried inside while their eyes smiled”: they felt upset but tried to hide that emotion from each other. “There was no turning back for two / Erase the memory stockpile”: the damage had officially been done to the relationship, so perhaps the protagonists felt the need to push happier memories out of their minds. Then the narrator offers one more unique use of the rollercoaster metaphor. “In the rollercoaster shadows” — in the moments following that terrifying, thrilling breakup — “they took off their shoes and bared their souls.” This final phrase doubles as an apparent allusion to breakup sex and as a bit of wordplay very typical of Früvous lyrics (souls/soles).

An additional verse preceding this one was never recorded, despite being printed in the liner notes for Wood (Example 2). This verse does away with the poetic riddles and amusement park analogies, leaving direct introspection in their place. Here, the narrator is analyzing the breakup that occurs in the chorus. Although the listener never actually hears this verse, knowledge of its existence certainly underscores the narrative communicated in the recorded song.

Example 2: Additional “Fly” verse printed in Wood liner notes.

Besides the amusement park imagery, these lyrics in “Fly” are notable for their frequent manipulation of narratorial voice. The song uses first-person, third-person, and even possible second-person voice throughout, often changing between lines. The narrator does feel a bit unreliable due to this constant shifting, but they come off as very sincere in their telling of this story. In fact, it is their status transformation and its context that make the lyrics feel so genuinely emotional.

The confusion about the narrator’s position in the story is mostly due to voice. The only personal pronoun in the first verse is the word “you.” This verse uses and reuses the word in a way that doesn’t feel like true second person, where it would be addressing a specific individual or group. Instead, it seems to be disguising some reflection or analysis on the part of the narrator. The additional, liner-notes-only verse utilizes “you” in the same way as the opening verse: to contemplate aspects of the human experience in an effort to understand the climax to which this relationship has come. In both verses, the word “you” could just as easily be the word “one,” albeit for more of a mouthful (Example 3). While it is initially unclear whether the narrator is making these observations from a close or distant proximity, further listening will indicate which is the case.

Example 3: First verse and additional verse rephrased with “one” instead of “you.”

The second verse opens in standard third-person voice to dictate the amusement park story. The use of “they,” “he,” “his,” and “she” leave little room for doubt as to the narrator’s proximity; the narrator has positioned themself outside of this story, as a sort of omniscient observer. Halfway through the chorus, however, something changes. The narrator uses “let’s,” which includes “us”; “we’ll,” which includes “we”; “our”; and then the big giveaway, “you and I” (Example 4). This sudden shift to first person scrambles the listener’s understanding of the narrator’s stance. One possible explanation is these last two lines are meant to be dialogue spoken by one of the protagonists to the other, but nothing in the printed lyrics or recorded song indicate this. The only other possible interpretation is that the narrator has indeed begun speaking in first person. These few pronouns signal that the narrator is directly involved in the story, and is one of the members of the couple. It feels as if the narrator has been trying to remain emotionally distant from this breakup, consciously pretending all along that they have no direct connection to the story. In these two lines, the narrator accidentally slips into an emotional reaction and gives themself away. The lines are spoken by a protagonist after all; it just so happens that this protagonist is also the narrator.

Example 4: Chorus with first-person language emphasized.

Now that the narrator is clearly a participating member in this narrative, the rest of the lyrics are reframed. The third-person material in the verses and chorus appear to be a fictionalization of the narrator’s own lived experience. The verses with the ambiguous “you” now also appear to reference back to the narrator. The reflection in these verses is introspective, the narrator’s exploration of their own feelings and experiences. Still, the address is a bit misleading due to the narrator’s frequent shifts in perspective. The narrator appears to be publicly addressing a broader audience during most of the song, including the disguised first-person “you” passages. But in “you and I” at the end of each chorus, “you” is very clearly a specific person: the other half of this couple, the other protagonist. This pointed address makes that specific line, if not the whole song, feel much more private.

All of this perspective-shifting points to a very indirect communication style from the narrator, who seems to be using a fictionalized couple and a metaphorical story to grapple with something very real and concrete that they feel. In this particular case, the narrator’s frequent changes in position do make them less reliable; these transformations could be read as somewhat deceptive. Still, their sincerity remains strong and unaffected. Their repositioning is not done out of malice, but rather out of a genuine attempt at self-protection and rationalization. If they can distance themself from the event, perhaps both the breakup and the lead-up to it will become easier to process.

The emotional revelations in the lyrics are only emphasized by the song’s harmonic content. Most of the tonality in “Fly” is relatively straightforward. The verses consistently point to A major being the tonic (Example 5). They are always harmonically open and on-tonic, although the first verse starts in second inversion with no bass (Example 6). So the basic chord progression in each verse is:

I - ♭VI - V / I - ♭VI - V / vi - IV - iii - ii / ii - ♭VI - V

The chorus, however, is much more ambiguous. The harmony in this section alternates between Em and either A7 or A, which — due in part to the build in both the vocals and the lyrics — feels like a ii - V progression leading to D major. Instead, the shuttle gives way to an unexpected Bmaj7 chord, which falls far outside of the tonal world in which Früvous has immersed the listener so far. This chord is no mistake; the root and fifth are outlined by the bass, and the tambourine doubles its accents in these measures (Example 8). Because of the harmonic, melodic, and lyrical buildup in the preceding lines of the chorus, the listener is prepared to hear a tonic at each of these points. When Früvous plays a strong, well-defined Bmaj7 chord, the listener is primed to accept it as a convincing arrival point. Still, the chord comes unexpectedly enough so as not to fully replace the A major tonic elsewhere in the song.

Example 5: First verse chord analysis.

Example 6: Opening inverted A major riff, used in isolation in first verse.

Example 7: Chorus chord analysis.

Example 8: Full transcription of Bmaj7 chord in chorus.

The tonal ambiguity in the chorus destabilizes the listener’s sense of tonality in the verses enough to call A major a fragile tonic, “in which the tonic chord is present but its hierarchical status is weakened” (Spicer, 2017, p. 1). Despite opening each verse and even the song’s introduction, A major is often inverted and usually lacking a third. It is further undermined by the Em and A7 shuttle, which seems to give it a different function. Finally, A major is almost completely dislodged by the finality of the Bmaj7 chord. The fragility of the A major tonic here is fitting: the moments before, during, and immediately following a breakup can be some of the most emotionally fragile times a person can experience. The complex bittersweetness of this particular breakup — between two people who “really love” each other (Moxy Früvous, 1997) — is also illustrated by the presence of both major and minor forms of E- and B- based chords (Example 9).

Example 9: Major and minor E- and B- based chords. Minor chords shown in rectangles.

The Bmaj7 chord also has another symbolic role. Bmaj7 coincides only with the words “fly” and “I” — “fly” as in escaping or being released from the relationship, and “I” in the recurring, repositioned phrase “you and I”. This harmonic departure from familiar material represents the protagonist’s departure from that same familiarity: from A to Bmaj7; from a troubled yet comfortable relationship to the single life. This is not to say that the new situation need be unpleasant or wrong in any way; the Bmaj7 chord — with C#, F#, and an occasional D# in the vocals, and twice as much tambourine as anywhere else — is a totally consonant, pleasurable experience. The Bmaj7 chord also uses two pitches (D# and A#) that don’t appear at any other point in the song. If the song can use new harmonic sounds in this way, who is to say what yet-undiscovered joy this freedom might allow our protagonists?

Every one of the implied artist’s choices in this song are intentional, from the constancy of the amusement park analogy to the status transformations to the tonal complexity. To listen to “Fly” is to experience the simultaneous heartbreak and liberation of the narrator through multiple avenues at once. In this way, this song tells an important story about an imperfect, unsteady relationship. It normalizes being honest with oneself and one’s partner, and reminds those in unhappy relationships that they deserve happiness — that sometimes, the best thing is to let go.

Bibliography

Burns, L. (2010). “Vocal Authority and Listener Engagement: Musical and Narrative Expressive Strategies in the Songs of Female Pop-Rock Artists, 1993–95.” Sounding Out Pop: Analytical Essays in Popular Music, ed. Mark Spicer and John Covach, 154–92. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Harvey, M. (1995). Interview with Moxy Früvous. The Peak, 91(1). Simon Fraser University (Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada). Accessed on Früvous Dot Com. https://www.fruvous.com/news/950905nw.html.

IMDb.com. (1956). As the world turns. IMDb. https://m.imdb.com/title/tt0048845/.

McLean, S. (2013). Moxy Früvous. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/moxy-fruvous.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Midway Definition & meaning. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/midway.

Moxy Früvous. (1995). Fly [Song]. On Wood. Warner Music Canada.

Moxy Früvous. (1997). Fly [Song]. On Live Noise. Bottom Line Records.

Spicer, M. (2017). “Fragile, Emergent, and Absent Tonics in Pop and Rock Songs.” Music Theory Online 23 (2). http://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.17.23.2/mto.17.23.2.spicer.html.

Wood. Früvous Dot Com. (n.d.). https://www.fruvous.com/woodlyr.html.